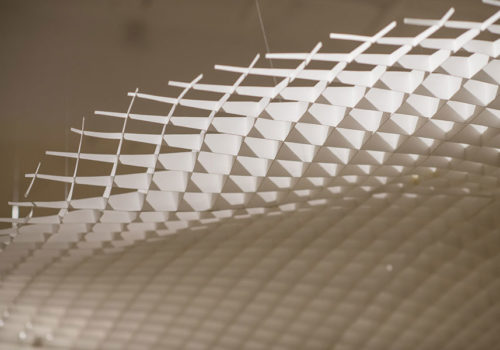

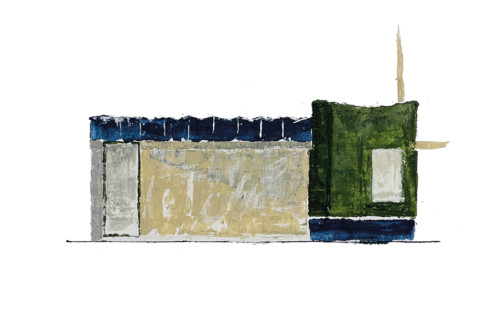

Ein schwebendes Dach aus Papier von Studio Maks

- Installation von Studio Maks, München, 2020 © Schelke Fotografie

- Installation von Studio Maks in der Ausstellung “Dialog Japan : Europa” | © Schelke Fotografie

- Installation von Studio Maks | © Schelke Fotografie

- © Schelke Fotografie

- © Schelke Fotografie

Ausstellung “Dialoge Japan : Europa”

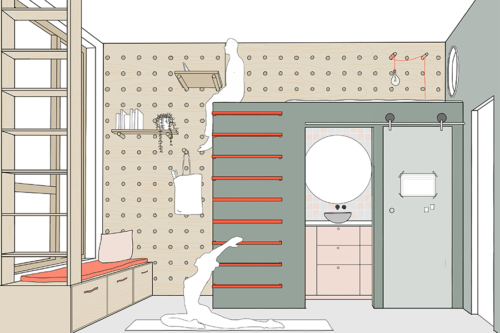

Im Zentrum der Ausstellung schwebt die Installation des niederländischen Büros Studio Maks. 288 handgeschnittene Papierstreifen wurden dafür vor Ort zusammengefügt, wie das kurze Video zur Installtion eindrucksvoll zeigt.

Inspirierend hierfür war das Phänomen der Hanami, der Kirschblütenzeit in Japan, bei dem sich das Stadtbild ändert und unter dem Dach der blühenden Bäume Picknicks und dergleichen veranstaltet werden. Die Installation mit ihrem schwebenden Dach bietet ebenfalls einen überdachten Raum, einen einladenden Ort für alle, ohne harte Grenzen zu schaffen.

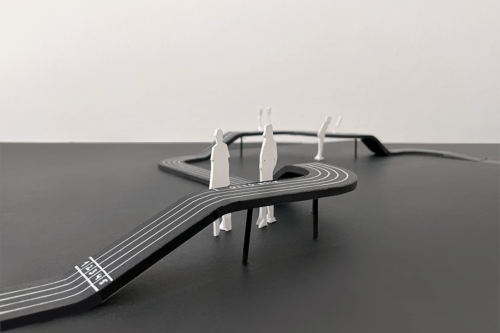

Das Modell nimmt Bezug auf die Stahldachkonstruktion des Entwurfs für das Besucherzentrum des Instituts für Technologie in Österreich, an dem das Büro derzeit arbeitet. Dünne Stahlelemente bilden die tragende Stahlkonstruktion, gleichzeitig filtern sie das Tageslicht in dem Gebäude und schaffen in seinem Inneren eine parkähnliche Atmosphäre. Das Besucherzentrum wird ein einladender, für alle Menschen offener Ort. Es ist ein Raum, in dem sich Erwachsene und Kinder treffen, um mehr über Naturwissenschaft zu lernen, aber auch, in dem der Einzelne in Ruhe die schöne Umgebung genießen kann.

Lesen Sie im Interview mit Marieke Kums, der Gründerin des Rotterdamer Büros Studio Maks, mehr über ihren Entwurf, die japanische Baukuktur und die Einflüsse der japanischen Kultur auf ihr Schaffen.

Q1: What is the idea underlying the design and how does it articulate itself in the design?

A space does not need much to become a place:

Like Hanami:

A soft demarcation overhead,

a line in the grass branches of a tree reaching out,

the sun momentarily creating a play of light,

People.

These were our thoughts when we created the design for this floating roof; it provides a covered space, an inviting place for all, without creating strong boundaries.

The model consists of 288 hand cut paper members.

The model resembles the steel roof structure of the design for the visitor center for the Institute of Technology Austria that we are currently working on. The thin steel members form the loadbearing steel structure; the same time they filter the daylight into the building, creating a park-like atmosphere in its interior.

The visitor center will be an inviting space, open to all people, situated in the middle of a park. It is a space where adults and children will meet to learn more about natural science, but also where an individual can quietly enjoy the beautiful surroundings.

Hanami (??, „flower viewing“) is the Japanese traditional custom of enjoying the transient beauty of flowers;

flowers („hana“) are in this case almost always referring to those of the cherry („sakura“) or, less frequently, plum

(„ume“) trees.

Q2: Is there a special experience that marks a key moment in your involvement with Japanese building culture?

I cannot answer for each person in our studio. But personally: I worked in Tokyo for several years, with SANAA / Kazuyo Sejima & Ryue Nishizawa. It was a very interesting period during which we worked on projects inside as well as

outside Japan. The office has a most open minded and experimental attitude towards architecture. It is constantly trying to define new ways of creating space in all fields of architectural design.

Eve Blau beautifully describes it in her essay on SANAA titled “Inventing New Hierarchies” for the Pritzker Prize Award in 2010: “Sejima and Nishizawa are concerned with exploring the cognitive possibilities of architecture, how the built work can impact the way in which we know our world and ourselves and the processes by which knowledge and understanding are acquired through experience. Analysis goes far beyond the functional considerations of program; it is based on intimate engagement with the details and dynamics of lived experience in all its multiscalar contemporary complexity.” This attitude towards architectural design has come to represent Japanese Building culture for me.

Q3: Which architect and building of Japanese culture (contemporary and historical) is most influential for you?

There is rather a set of ideas, of spatial thinking that interests us. Firstly, perhaps, the sensitivity with which changes in society are represented in spatial design concepts, as Eve Blau described in her essay. This sensitivity seems present in

the work of many contemporary Japanese Architects. Secondly, the notion between private and public spheres that is continuously re-examined, re-negotiated, re-invented. Thirdly, the fluidity of the functional programming of space

and the spatial freedom the users often enjoy. Fourthly the poetic relationship with nature, or to be more precise; the cultivation of nature for the purpose of integrating it into the humanmade world. Perhaps lastly, the high level of dedication to the process of creation, the level of detail in the design and construction. Many of these aspects are important for the work of our studio too and are represented in our projects, such as our “Table studies” and the projects for “Park Vijversburg”.

Q4: Is there a vernacular architecture of this culture (contemporary and historical) that inspires you?

An inspiring example is the house of Moriyama-san, designed by Ryue Nishizawa. It is situated in a residential neighborhood on the outskirts of Tokyo. Moriyama-san used to own a liquor store. He wished to retire and refrain from public life. But instead of building a hermit’s dwelling, Nishizawa designed a most open, integrated living community

on Moriyama-san’s land. Here he could live surrounded by friends, make new acquittances weekly.

Instead of living a withdrawn retirement-life, Moriyama-san remains a well-respected person in his community. The project is a beautiful example of Japanese building design and craftmanship, but also represents a shift in thinking from the traditional towards contemporary way of living in Japanese culture: the traditionally private house turned inside

out. At the same time, it shows a profoundly optimistic attitude towards architecture and what it can do to transform people’s lives.

Q5: Are there essential differences and commonalities between the two building cultures?

There are too many note-worthy differences and commonalities between the Japanese and European building cultures to describe here in only a few words. What seems very interesting though is the way in which Japanese architects have been able to preserve a unique place in the contemporary architecture scene, despite all the differences and commonalities, and despite the globalization processes at play. And it is not just now; throughout history Japanese architecture, weather it was

traditional, modern or contemporary, has always been able to reinvent itself and be at the forefront of the architectural scene in one way or another. This, one must admit, is quite remarkable.

Studio Maks, NL-Rotterdam

Studio Maks wurde von Marieke Kums gegründet. Das Büro schafft intuitive Raumgestaltungen in unterschiedlichen Größenordnungen: von der Gartengestaltung über den sozialen Wohnungsbau bis hin zu Möbeln. Das Studio strebt eine fließende, programmfreie Architektur an, die alle Arten von Aktivitäten im Laufe der Zeit ermöglicht. Die Arbeit untersucht die Beziehung zwischen Mensch, Natur und Technologie neu und befreit die Architektur von euklidischen Geometrien und vorgefassten Realitäten. Das Studio wurde mit zahlreichen Preisen ausgezeichnet. Zuletzt wurde die Arbeit von Studio Maks für den Internationalen Preis der Europäischen Union für zeitgenössische Architektur – Mies-van-der-Rohe-Award – nominiert. Marieke Kums studierte am Massachusetts Institute of Technology und an der TU Delft, wo sie ihr Studium erfolgreich abschloss. Anschließend arbeitete sie mehrere Jahre bei Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa / Sanaa in Tokio.

Studio Maks was founded by Marieke Kums. The office creates intuitive spatial designs at every imaginable scale: from garden designs, to public housing and furniture. The studio aspires to make a fluid, more program-free architecture that allows all kinds of activities to take place over time. The work re-examines the relationship between, men, nature and technology, liberating architecture from Euclidean geometries an d pre-conceived realities. The studio has been awarded numerous prizes. Most recently MAKS’s work was nominated for the International European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture – Mies van der Rohe Award. Marieke Kums studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the TU Delft, from which she graduated. After her graduation she worked several years with SANAA / Kazuyo Sejima & Ryue Nishizawa in Tokyo.

Weitere Informationen zur Gruppenschau sowie eine virtuelle Führung durch die Ausstellung finden Sie hier.

Kuratiert wurde die Ausstellung “Dialoge Japan : Europa” von Kristina Bacht und Çi?dem Arsu-Minuth (AIT-ArchitekturSalon) in Zusammenarbeit mit Nils Rostek (Kollektiv A).