Lara Grandchamp

Lara Grandchamp – Collection of ethnographic objects of the Swiss TPH

This term, my group of study is giving a closer look at the eclectic collections of objects gathered over the years by the The Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH).

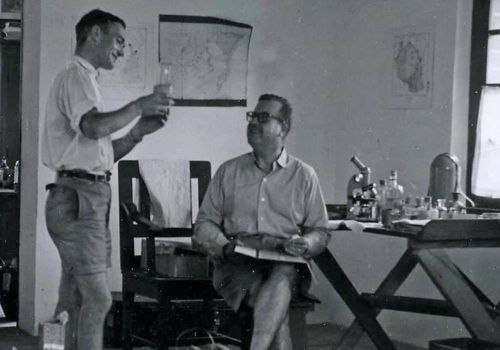

The Swiss TPH was founded in 1943 by the famous Basler zoologist Dr Rudolf Geigy[1].

Over the years, Dr Geigy and his fellow scientists colleagues have brought back different objects and art pieces from the countries they have stayed in mainly western Africa. These objects have since taken random placed in the TPH’s building, with no particular care in terms of display setup. It was rather amusing to see wooden mask and spires casually hanged beside the printer and the bathroom door!

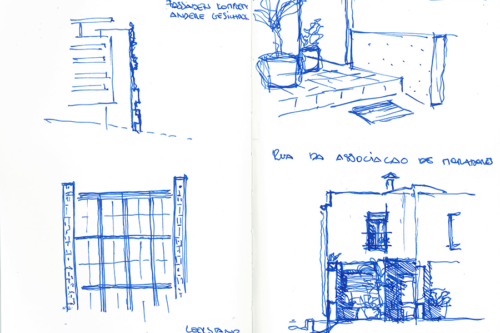

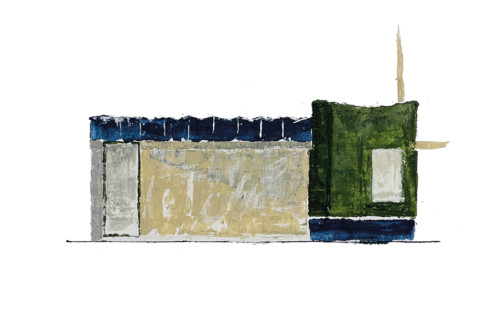

As the Swiss TPH will be soon relocating into their new building, “Belo Horizonte”, which should be completed in 2021, the question on what would happen to these objects came on the table. What are their actually significance and value to the institute? The people who brought them back being either retired or having passed away, the memories and emotional link to them isn’t there anymore. For the members of the staff, walking past them everyday, these objects are just random, dusty, African souvenirs.

At first, we wondered if the question of restitution of African art [2], developed by French art historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese writer Felwine Sarr (in their report commissioned by French president Emmanuel Macron, in November 2017 [3]) should be considered. But the nature of the collection made it clear it wasn’t relevant in this case, as these objects were bought directly to the craftsmen’s shop, or were given as gifts by the local people.

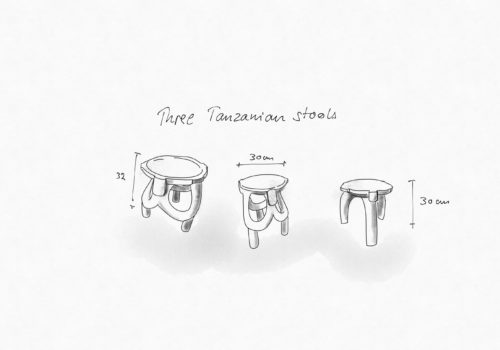

Having to come up with a proposal for a potential scenography for some of pieces of the collection, I spent some time thinking of possible narratives that I could use. However, from all these objects, three Tanzanian wooden stools caught my interested in particular. Being an amateur of chairs and stools, I was charmed by the beauty lying in their pragmatic design. These stools can be found in most Tanzanian households, and aren’t meant to be showpieces of furniture. Their design has remained the same for the last centuries, as they are still being built following traditional designs.

Stools are the oldest piece of furniture been produced and their use is worldwide. Going through their history, I found very interesting on how it is present in every culture, and how their conception didn’t in fact varied that much from a country to another. I like to see them as a hyphen between cultures and social classes across the world. A symbol of equality.

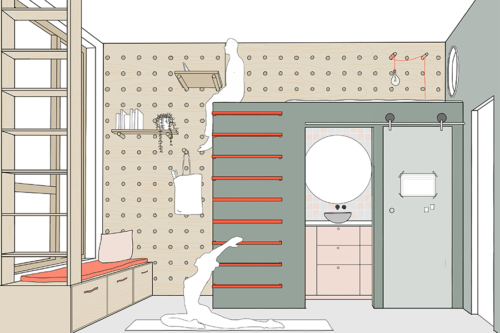

During my research, I came across interesting aspects that didn’t really cross my mind before: How much interior architecture is influenced by the height of a seat.

In this book Now I sit me down [4], what architect Witold Rybczynski brought to light is that whether you live in a floor-sitting or chair-sitting society has an impact on much more than how you sit. It can influence everything from your clothing to your house layout to your muscle development, he writes: « If you sit on floor mats, you are likely to develop an etiquette that requires removing footwear before entering the home. You are also more likely to wear sandals or slippers rather than laced-up shoes, and loose clothing that enables you to squat or sit cross-legged. Floor-sitters tend not to use tall wardrobes—it is more convenient to store things in chests and low cabinets closer to floor level. People who sit on mats are more likely to sleep on mats, too, just as chair-sitters are more likely to sleep in beds. Chair-sitting societies develop a variety of furniture such as dining tables, dressing tables, coffee tables, desks, and sideboards. Sitting on the floor also affects architecture: walking around the house in bare feet or socks demands smooth floors—no splinters—preferably warm wood rather than stone; places to sit are likely to be covered with soft mats or woven carpets; tall windowsills and very tall ceilings hold less appeal. Lastly, posture has direct physical effects. A lifetime of sitting unsupported on the floor develops muscles not required for chair-sitting, which is why chair-sitters, unaccustomed to sitting cross-legged, soon become uncomfortable in that position. And vice versa. People in India regularly sit up on train seats and waiting-room benches in the cross-legged position, which they find more comfortable than sitting with feet hanging down. »

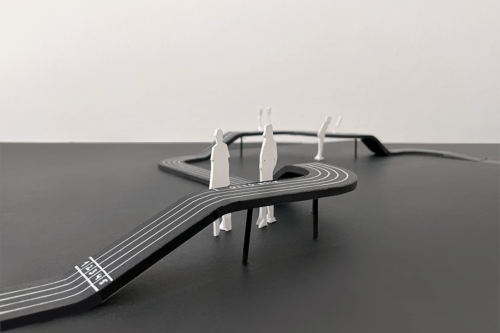

For the next step of my semester work for the Swiss TPH, I will work on a proposal, which suggests starting a collection of stools coming form the different countries they have offices in (more than 20), and also collaborate with (almost two hundreds!). And of course, the starting point would be the Tanzanian stools.

This collection could be the symbol of the unity that is a key value of the Swiss TPH. Through these little stools – portraying so well human presence -, everyone is place at the same level of worth.

I look forward to developing this project further and tell you more about its outcome, in January.

[1] https://www.swisstph.ch/en/about/swiss-tph-history/

[2] https://www.africanews.com/2018/12/03/the-thorny-question-of-the-restitution-of-african-art-this-is-culture/

[3] https://restitutionreport2018.com/sarr_savoy_fr.pdf

[4] RYBCZYNKSKI, Witold. Now I sit me down: from klismos to plastic chair: a natural history. New York: New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017. 242 p.